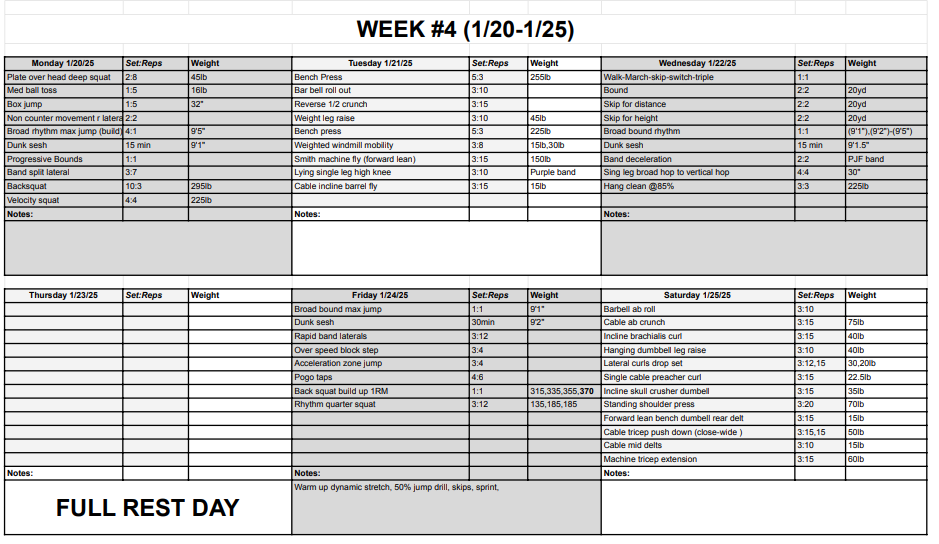

I’m deep into my dunk journey, and this week was a rollercoaster. Plyo days were solid—I hit my Monday, Wednesday, and Friday sessions like clockwork. But Thursday? Thursday, I was cooked. My plan was to go in for some rehab, core, mobility, and stability work, but my body had other ideas. Instead of forcing it, I just rested, and honestly, sometimes that’s the best move you can make.

The Dangers of Overtraining: More Isn’t Always Better

It’s easy to think that more work equals more gains, but there’s a point where you’re just digging yourself into a hole. Overtraining is real, and if you don’t respect your body’s need for recovery, you’ll end up stalling—or worse, regressing. Research published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that excessive fatigue impairs motor unit recruitment, meaning your muscles literally stop working as efficiently. Another study in Sports Medicine highlighted how overtraining leads to prolonged recovery times, decreased power output, and even hormonal imbalances.

Long story short: if you feel like a zombie, don’t try to train like an Olympian. Sometimes, the best thing you can do for your gains is to take a nap.

Squatting for Vertical Gains: The Angle-Specific Approach

This week, I also hit back squat multiple times and even attempted a one-rep max. Not a true powerlifting squat, though—I’m training for jumping, not a powerlifting meet. And that means focusing on angle-specific strength.

Research in the Journal of Applied Biomechanics shows that training at joint angles specific to your sport leads to better force production at those angles. Translation: if you want to jump higher, train your squat at your jump-specific knee angle. Going “ass to grass” is cool for general strength, but it doesn’t translate directly to jumping, where your knee angle is much shallower. Plus, taking forever to get out of the hole wastes time, and the key to jumping high is spending as little time on the ground as possible.

Strength vs. Speed: Why You Need Both

Plyos are crucial—probably the most important part of the equation—but there’s a ceiling. At some point, you have to ask yourself, do I even have enough horsepower to get off the ground any higher? That’s where strength training comes in.

A study in The Journal of Sports Sciences found a strong correlation between maximal squat strength and vertical jump performance. Basically, the stronger your legs, the more force you can put into the ground, and the higher you go. But it’s not just about raw strength—there’s a balance. Research from The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) suggests that once you can squat 2 to 2.5 times your body weight, additional strength gains don’t provide as much of a return for your vertical jump. So, if you’re squatting barely over bodyweight, you have a ton of room to grow. If you’re already squatting double your body weight, it’s time to focus on speed-strength and plyos.

The Takeaway: Train Smart, Not Just Hard

You can get your little chicken legs firing as fast as possible, but at some point, you’ll need to upgrade to a stronger set of legs. My plan? Keep balancing plyos with strength work, train my squat at the angles that matter, and listen to my body when it needs rest. Dunking isn’t just about jumping—it’s about training the right way, recovering well, and stacking small wins over time.